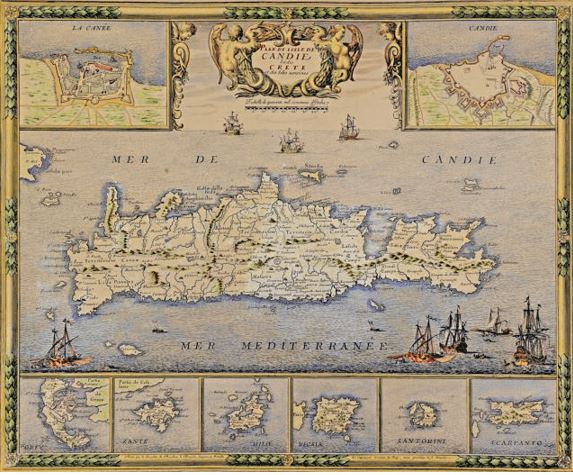

After the fall of Constantinople in 1453, the centuries that followed were characterized by bloody clashes between the Venetians and Ottomans, who fought for sovereignty over the seas, while piracy was a major threat to safe navigation. Pirates of every nationality ravaged the Greek seas.

Ottomans from the coast of Asia Minor and pirates from North African areas Tunis, Algiers and Morocco were active in the 15th and 16th centuries. Moreover, in the early 16th century, the notorious Chajredin Barbarossa, like a whirlwind, sowed terror and havoc in the Aegean and Ionian Seas through raids and looting while he captured thousands of Greeks and consequently, many islands were deserted.

European pirates, mostly French, Spanish, Italian, English and Dalmatians also engaged in the Greek seas. Sometimes they fought against the Turks, while other times they ravaged the islands thus, gaining an enormous wealth and glamour.

The advent of burgeoning Greek commerce

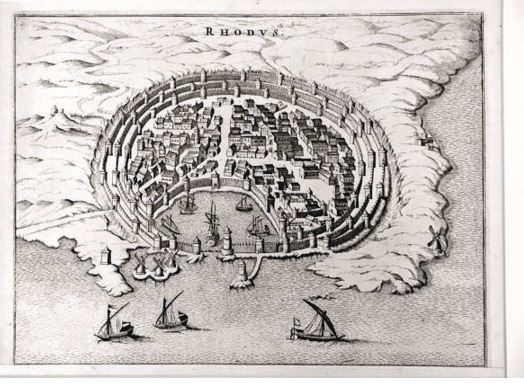

The most notable however of all the Christian pirates, were the Knights of Saint John, who were monks and warriors at the same time. Until 1522, they were based at Rhodes and the other Dodecanese islands. From 1530, their base became Malta. They turned into relentless persecutors of the Ottomans although, many times they themselves turned against the Christian populations of the Aegean Sea, causing huge disasters.

Nevertheless, sporadic testimonies inform us, that Greek islanders were either merchants and captains or crew members in Constantinople, the Black Sea, and ports of the Aegean and Ionian Sea, while they were considered to be the best shipbuilders in the Ottoman and Venetian shipyards.

Gradually, with the encouragement and support of the Ottoman state, a class of merchants who dealt with the empire’s domestic trade developed. The Greeks, Ottoman subjects, owned small vessels for handling trade, between the islands, mainland Greece and Asia Minor. At the same time they maintained a small-scale long distance trade with Central and Western Mediterranean as well as Northern Europe that gradually expanded to more remote destinations. The Ottoman Empire’s transit trade with the West at the time was handled by foreigners. The Ragouzaioi1 and Venetians had a monopoly, at least until mid-16th century when the French initially and later the English appeared in the region. The Ottoman Empire by adopting the system of capitulations had granted significant privileges to foreigners thus, consolidating their presence at major trade centers.

The international situation and conditions

In the 17th century, the foreign trade of the Empire was still managed by the English, French as well as the Dutch, whose role in the transit trade of the Mediterranean became quite significant during this period.

Under these conditions of eradicating competition between the foreign naval forces, the Greeks gradually began to grow. The establishment of Ottoman rule over the islands and their colonization program followed by the Ottoman state, in conjunction with the granting of benefits to the inhabitants, led many of them in semi-autonomous status. These conditions created the appropriate presuppositions not only for the demographic growth of the islands, but also for their economic rise. The revival of the Aegean economy was the key to the development of maritime activity. Already, in the 17th century the limited presence of Greeks in international trade began to grow, filling the void of the shrinking shipping of Venice.

In the Ionian Islands shipping was not allowed to develop during the Venetian occupation. Venice’s interventionist and monopolistic policies did not allow the development of local shipping, despite the fact that the necessary funds and know-how existed. After the end of the Venetian domination and the French occupation in 1797 the shipbuilding and sea trade experienced an exceptional growth.

During the first decades of the 18th century, and in particular after the Treaty of Utrecht (1713) and the peace that prevailed over the European countries, till the American War of Independence (1775-1783), the French dominated over the Mediterranean and especially the trade of the Levant. The export activity of the eastern Mediterranean ports such as Izmir (Smyrna) and Alexandria, had attracted their interest already since the 17th century.

The eastern Mediterranean ports constituted for the West trans-shipping stations for goods that arrived with caravans from Persia, India, Cappadocia, Armenia, the Arabian Peninsula and Africa. Thus, at the beginning of the 18th century, France had set up an extensive network of commerce dealers in the Eastern Mediterranean.

The Greeks initially took advantage of the Ottoman Empire course, starting from the Pasarovitz Treaty (1718) that marked the end of the Venetian – Ottoman conflict and the beginning of a period of tranquillity in the region.

Special agreements of the Austro-Hungarian-Ottoman Treaty liberated trade between the two empires and gave special privileges to Ottoman subjects contributing to the prosperity of the land and sea trade.

A historic milestone in the rise of Greek Merchant Shipping was the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca (1774), that ended the first Russo-Ottoman war (1768-1774). The significance of the victory of the Russians over the Ottomans was paramount for it led to the commercial opening of the Black Sea and the spread of grain crop cultivation. The Greeks, initially taking advantage of Russian protection by raising the flag of Russia, began to dominate over maritime trade between the Black Sea and the Mediterranean and gradually evolved into an international factor in the trade of the Eastern Mediterranean.

The view that the use of the Russian flag permitted by the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca as a decisive growth factor for the Greek shipping industry is not confirmed by the available data. The use of the Russian flag was expensive and there are numerous examples that long after 1774, Hydra’s residents continued to buy Malta’s protection. On the contrary, the grain trade at the Black Sea coastline that was almost exclusively run by Greek shipping houses that established their bases at Taganrog, Odessa, and other similar places, appears to have had a truly favourable flourishing effect on shipping according to the Russian Archives.

During the Second Russian-Turkish War, the French Revolution (1789) began, which contributed to the decline and withdrawal of French trade and maritime sovereignty in the Eastern Mediterranean and its succession by the British. At the same time, a 20-year period of continual wars began in which all European countries were involved. Naturally, the Mediterranean was a central point of conflict and strategic redeployment, as Mediterranean trade continued to be a major factor in international economic relations.

A peak period of dominance

These geopolitical turbulent conditions helped in the growth of Greek merchant shipping and the creation of nearly a monopoly of the grain transport from the Black Sea to the Mediterranean ports.

It should be mentioned characteristically that in the period 1792-1806, the number of Greek-owned ships engaged in trade in the Black Sea reached nine hundred ninety-three. This increase was also due to the policy of the Ottoman Empire that encouraged Greek subjects to meet the ever-growing needs of Constantinople and the Mediterranean ports for grain crops.

Given that Greek shipping supported its growth mainly in the grain trade, it is understandable that the demand and product price influenced respectively its growth rate. Thus, during the years of the European wars, the demand for grains and its price in the European markets was high and it could be attributed to the sense of insecurity cast over the populations. On the other hand, prolonged periods of peace had a negative effect. Of course, the lack of grain produce due to natural causes, such as a production disaster or oversupply due to overproduction, had similar effects and had a grave effect on the entire commercial system, even in terms of social relations between the countries of produce and the areas of the produce’s consumption.

Napoleonic War period

The peak in the rise of the Greek Merchant Shipping was observed during the period from the American War of Independence (1775-1783) until the end of the wars of the French Revolution (1792-1802) and the Napoleonic Wars (1792-1815).

The Greek fleet remained neutral and thus, exploited the trade collapse of the French in the Mediterranean. Consequently, its presence in Western Europe became noticeable. By the end of the Napoleonic Wars, the Greeks had doubled the number and size of their fleet and managed to establish their presence in the large trade of Mediterranean grain crops and hence, earned great fortunes.

Greek gains increased further as the Greek-owned fleet became actively involved in supplying France with food staples during the Napoleonic Wars. To date, there was a perception that the port of Marseille was France’s main catering port. However, recent studies are focusing on the break-up of the blockade taking place mainly in the ports of Italy. The Greek ships along with the ships that originated from Ragusa first arrived at Livorno and Genoa and then had the grain crops transported to the French ports via smaller local boats.

Finally, it should be noted that the rise of Greek shipping in the Eastern Mediterranean and its spread throughout the Mediterranean and beyond took place concurrently with the rise and dominance of the Greeks in overland trade in South-Eastern Europe among the Ottoman, Habsburg and Tsarist Empires. The ports of Constantinople, Thessaloniki, Smyrna, Alexandria and other smaller ones became the exit gates, terminals, for land-based routes.

Ionian Islands

The Ionian Islands fleet played an important role in the development of ocean going Greek shipping. The Ionian Islands under Venetian rule, as well as the ports of the Greek western coast that were under Ottoman rule, had already commercial ties with Venice, Ancona, Seningalia, Trieste and Livorno since the beginning of the 18th century. All the while the Aegean fleets were limited mainly to intra-Ottoman regional and local trade.

The fleet of the Ionian Sea supplied the ports of Central and Western Mediterranean with foodstuffs, mainly grains, raw materials (timber) and local craft products. The main emerging destinations were Cephalonia and Messolonghi and followed by Zante, Galaxidi and Ithaca, while the most important economic centers became Corfu, Preveza and Patras. By 1860 the opening of the Black Sea led the merchant fleet to a great development, during the end of the 19th and early 20th century. The ports of Corfu, Zante and Argostoli evolved into key junctions of the Mediterranean trade routes.

Aegean Islands

The Aegean shipping, as already mentioned, maintained its autonomy until the middle of the 18th century and was limited mainly to the internal trade of the Ottoman Empire. However, from the middle of the 18th century the Aegean fleets took advantage of the wars of the French Revolution (1792-1802) and the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815) and began to travel all over the Mediterranean Sea. It is indicative that after 1759 the presence of the Aegean ships in Central and Western Mediterranean showed a significant increase, that peaked after 1790. After 1780, in the region of the Aegean, grain crops were the principal product of cargo handling. It is characteristic that in 1797, 34.4% of the ships with starting point the Aegean Sea transported only grain crops to the ports of Livorno, Genoa and Malta.

The North Eastern Aegean region is an important region for international trade for it connects the Aegean Sea and Eastern Mediterranean with the Black Sea. In the region of the Eastern Aegean, Psara, emerged as the dominant shipping center and from 1770 onwards has been the hub for the westward grain crop exports from the Black Sea, the Pagasetic Gulf and the coast of Asia Minor. Constantinople followed in the distribution of grain crops and operated mainly as a principal port for exports to the neighboring regions of the Balkans and Asia Minor, while it played a role as a distribution center for import trade.

The ships from Psara arrived at the North African coasts, Malta, Livorno, Marseilles, Barcelona and Lisbon, but also England and Amsterdam. The island’s merchant fleet in the last decade of the 18th century numbered seventy-eight vessels, accounting for 8% of the entire fleet of the Greeks.

Kasos and Patmos with the greatest tradition of interconnections with the Adriatic Sea and the Western Mediterranean, as well as Chios in the late 18th century were all places with great nautical tradition in the region, while Thessaloniki was a major financial and commercial center.

Hydra and Spetses

On the other hand, the Western Aegean is dominated by the shipping hubsof Hydra and Spetses, whose fleets play an important role in the transport of grain crops coming from the Pagasetic. Meanwhile, in the central Aegean Sea, Santorini and Mykonos stood out as they were engaged in the transit trade of grain crops from the Black Sea.

The shipping activities were not governed by any specific written legal framework. Local customs and habits applied on every island and in the large Mediterranean ports. In 1804, the first Governor of Hydra, George Voulgaris, attempted to fill the void with the adoption of the Hydric Maritime Law, that included all the rules that were hitherto customary.

The law empirically regulated issues related to ship ownership, crew, charter, loans interests and general trading issues. It was the first attempt to establish rules for the operation of shipping. After 10 years, in 1814, a similar law was enforced in Spetses.

Ioannis Paloubis, Vice Admiral (ret.), H.N

![ΕΒΕΠ: Οι επιπτώσεις από μια δυσμενή εξέλιξη του «δασμολογικού πολέμου» μεταξύ ΗΠΑ – ΕΕ [γράφημα]](https://www.ot.gr/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/ot_trump_EE25-1200x703-1-1024x600-1.jpg)

![Ακτοπλοϊα: Αυξημένη η κίνηση τον Ιούλιο παρά τα υψηλές τιμές στα εισιτήρια [πίνακες]](https://www.ot.gr/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/EV_BR_030918_APERGIA_PNO11-1024x683-1.jpg)